The Hine's Emerald Dragonfly

(Somatochlora hineana)

Distribution:

Hine’s emerald dragonflies are found in small, isolated populations that are heavily fragmented due to human encroachment and development. In the United States, they are currently found only in Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Missouri. Their distribution is limited because Hine’s have specific habitat requirements that must be met in order to allow them to survive. Hine’s require spring or seep-fed streamlets that are clean and cool, dry for part of each year, and are underlain by dolomitic rock.

Larvae:

Hine's emerald dragonfly larvae live in very small streamlets and shallow wetlands. These small habitats are often overlooked, even by most scientists. Hine's habitat typically dries for 1-2 months in the summer. Because it is so shallow, it freezes solid in the winter. For an animal that needs to live in water, that can be a little rough. There are advantages, though. Most dragonfly larvae of other species, as well as other predators that would feed on the Hine’s emerald larvae, die during these dry cycles, reducing the number of species Hine's must compete with for food and shelter.

One of the secrets to the survival of Hine’s emerald larvae during dry periods and winter months is the presence of burrowing crayfish. Larvae take refuge in these extensive burrows until conditions improve above ground. How they remain undiscovered and uneaten in burrows with crayfish that will readily consume them is still being studied.

Hairy! -not just for looks!

Hine’s emerald larvae are practically fuzzy! The hairs attract water and reduce the movement of dry air around their bodies when they are out of the water. This means that larvae can walk, breathe, and survive out of water for a time!

The larvae have a protracted larval stage lasting 4 to 5 years. During this time they feed on small aquatic organisms such as isopods, midge larvae, and amphipods. During the late summer of their 4th or 5th year, they crawl out of the water on a plant leaf or some other structure and emerge as an adult dragonfly. This is a dangerous time for an emerging adult because even a stray gust of wind can knock it off its perch, resulting in death or deformity.

Adults:

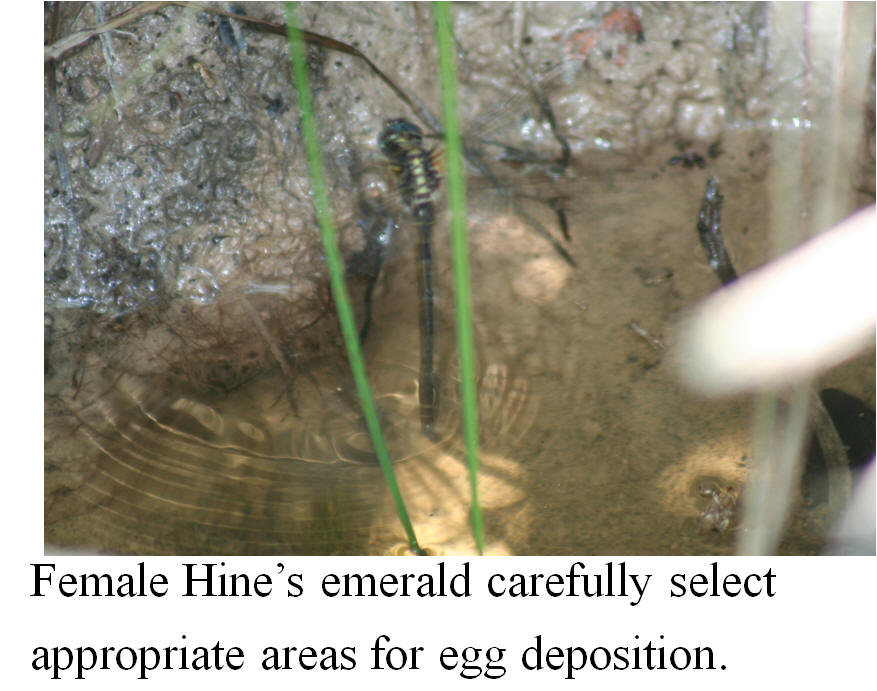

During the months of June and July, Hine’s emerald larvae transform into beautiful adult dragonflies. During this time they feed on various small flying insects they capture while on the wing in and around the spring-fed wetlands in which they breed; however, much of the time males and females occupy different habitat areas. Males patrol breeding territories located within and above clearings of cattails and streamlets. Mating occurs in flight when a female enters a male’s territory. The male grasps the female, and they form a “wheel” position. The pair can remain in this position for over 3 hours. To avoid unwanted matings and the time and energy they use up, females avoid areas where the males are until they need to lay eggs. After mating, the females will lay their eggs in the small streamlets by either depositing the eggs in the water or by placing them into the mud along the edges of the streamlets. The eggs will overwinter in the mud and then hatch the following spring as the water temperature increases, beginning the cycle again.

Why should we care about the Hine’s emerald dragonfly?

Preserving biodiversity is crucial to our own survival. Loss of species is an indication of the poor health of the ecosystems we depend upon. Which species are fundamental in maintaining an ecosystem is often not understood until they are gone.

The Hine’s emerald dragonfly is the product of over 300 million years of evolution. There were dragonflies flying over 100 million years before our remote primate ancestors walked the earth. There were Hine’s emerald dragonflies flying here before the continental icesheets carved out the Great Lakes. Surely, such an exquisitely designed and beautiful creature deserves not to be driven from the last few places where it can live.